Life with Will

|

|

|

three facsimile

pages of the

Observer Magazine 8 May 1977 |

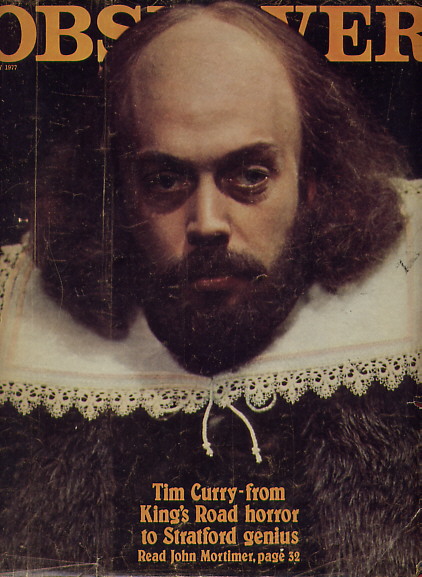

JOHN MORTIMER has just finished six plays on Shakespeare's life

which will be shown by ATV in the autumn. He was an apt choice to dramatise

versatile creative genius, embodying as he does the roles of playwright,

journalist, screen writer, critic and Queen's Counsel. Here he describes

his search for Shakespeare.

My enthusiasm for

Shakespeare is buried deep in my childhood. My father was always a passionate

addict of the plays. Instead of 'The Three Bears' I got Macbeth at his knee,

and I still remember screaming as his finger pointed out the blood‑boultered

Banquo in a corner of the sitting‑room. Later we used to see every play at

Stratford (at a time when Donald Wolfit was the star) and I remember being

paralysed with fear at the sight of a hooded figure in the hotel bedroom

which I took, at the age of seven, for old Hamlet up from the grave, until

I realised it was my reflection in the wardrobe mirror, pulling my shirt

over my head.

When he came to

see me at school my father would greet me with inappropriate Shakespearean

quotations. 'Is execution done on Cawdor?' I remember him booming for all

to hear, on a rare visit to Harrow speechday. In the holidays I paid him

back by performing 'Hamlet' and 'The Merchant of Venice' in the sitting‑room,

and as I was an only child I had to duel with myself, cheat myself of my

own pound of flesh, force myself to drink my own poisoned chalice and quarrel

with myself as my own mother. For this reason I still have great chunks of

the plays by heart and will recite them at bad moments in Law Court corridors.

So for almost 50

years my head had been full of the plays, but the life? When, in January

1976, I was asked by ATV if I would write six plays about Shakespeare, on

a schedule that would give me about four weeks a play, the idea filled me

with an equal mixture of enthusiasm and panic. How could I cope with his

biography ? I asked Professor Terence Spencer of Birmingham whom I'd met

at the National Theatre.

He assured me happily,

'You can write it all on a postcard.' This news came to me as a relief.

The plays would have to be works of fiction: six stories of what it might

have been like to be a dramatist in that hot summer of the English stage,

with no very clear hope of surviving the plague for another year, or the

closure of the theatres, let alone of struggling on to write 37 plays embalmed

in print to enthral audiences and bore examinees for all eternity.

Fiction is what

I would have to produce, but fiction founded on the facts about a character:

and if Professor Spencer were right, and the date of the marriage, the leases

for the transfer of property, the few lawsuits and the detailed will were

all history had to say on the subject of Shakespeare surely the works would

be more revealing. It's true that you can find almost any sort of Shakespeare

you want in the plays. Would you care for a radical reformer? ('Handy Dandy,

which is the justice. which is the thief?') Or do you prefer a Conservative?

('Take but degree away, untune that string and hark what discord follows.')

But the Sonnets, however interpreted, must be a great and agonised autobiography,

and I thought the plays, if no guide to their author's polities, at least

show certain obsessions. Ingratitude is a subject that aches through Shakespeare

like an old wound: and the Shakespearean hero has always one quality the author

admires, a Stoic acceptance, when the last battle is lost, of his own character,

flawed as it is, and his destiny. Jealousy is also a recurrent theme, as

are pride and ambition. These great and alarming concerns might, I hoped,

prove better material for six plays than the courtship of Anne Hathaway, or

the doubtful legend of the young poet poaching the deer at Charlecote.

When I talked to

Peter Wood, the director, he seemed doubtful. The character was still unclear,

and the plays only vaguely intentioned. 'It's like trying to pick up a handful

of water, he said. All the same we arranged to meet

at breakfast the next morning (we found later we shared many tastes, not

least that for getting up at around six and then playing records of Mozart

piano concertos very loudly and thus making life hell for our nearest and

dearest). 'The trouble has always been,' Peter Wood said, 'that Shakespeare

comes out so patient and long suffering. Like bloody St Francis of Assisi.'

So we began to evolve young, lying Shakespeare, who made terrible unfounded

boasts about his life in the theatre. And we went on to talk about Elizabethan

England as passionate and secretive and full of plots and pride and taboos

as present‑day Sicily.

Our first invention

was a steward for the Dark Lady, half Malvolio and half Pandarus, who would

thread his way with a sort of voyeur's ecstasy through the web of jealousy

and intrigue. By the time we had woken up the neighbourhood, and tired men

were going to work down Warwick Avenue Tube Peter Wood gave my working on

the plays his Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.

I was due to take

a trip to Sri Lanka, and in that improbable location I made a start with

the third play, the triangular relationship between Shakespeare, his Dark

Lady and his young patron the Earl of Southampton. I sat by the hotel pool,

listening to the delighted screams of Qantas air hostesses on a stop‑over,

and re‑read 'Troilus and Cressida' and the Sonnets. The story of the obsession

with a woman who had no idea of the havoc she caused, the loss of innocence

and friendship, the deep sexual disgust, was clear. As the conflicting claims

to being the Dark Lady still seem to me unproved I decided to invent her,

and made her a judge's wife whose husband was always busy hanging people

on circuit. Shakespeare, I hoped, was slowly becoming more than a list of

facts on a postcard.

I had begun work.

From then on I was to receive, at regular intervals, unsolicited propaganda

from the Francis Bacon Society. It wasn't, of course, as easy as that. I

began to discover that the known facts about Shakespeare's life would need

a pretty big postcard. They take some 260 pages of the best and most down‑to‑earth

of books on the subject, Professor Schoenbaum's 'Documentary Life', where

you may find facsimiles of all the documents, eked out, it must be said,

by some of the carefully distinguished rumours which began to be circulated

about Shakespeare after his death. It's as much as might be known about

a successful Elizabethan businessman, and there's no doubt that a perfectly

clear and coherent character emerges. There was obviously a William Shakespeare,

son of a Stratford glove maker and alderman, who got trapped into marriage

with a woman a good deal older than he: Anne was 26 when he was about 18.

He fathered three children, two girls and one boy, Hamnet, who died at the

age of 11. The year after Hamnet's birth Shakespeare left Stratford and disappeared

into those convenient 'dark years' during which he

might have been a soldier, a lawyer's clerk, a schoolmaster, or gone to Italy,

or picked pockets, or indeed have done whatever his admirers would most prefer.

In about 1589 he's heard of at the theatre, and a story put about after his

death has it that his first job was looking after the gentlemen's horses

while they were at the play.

Soon, however,

he got work as an actor, and then as a mender of old plays and writer of

his own chronicle of Henry IV. He became steadily more successful and prosperous,

but never wholly severed his ties with the country and his family, to whom

he returned, rich and famous, to retire and die in 1616.

Professor Schoenbaum can

show us with his facsimiles the externals of an actor‑writer's life, his

property buying, his unexpected path to the coat of arms of gentility and

financial success. What he cannot do is tell us what Shakespeare felt about

these matters, or why such an apparently calm course was forever inwardly

troubled with storms of bitterness, self‑hatred and rejection of the world.

Such things can only be speculated on and written about, not with the assurance

of history, but with the liberty of fiction. What remains certain, as someone

said, is that if the plays were not written by Shakespeare, then they were

written by a character who followed precisely the same career, and happened

to have an identical name.

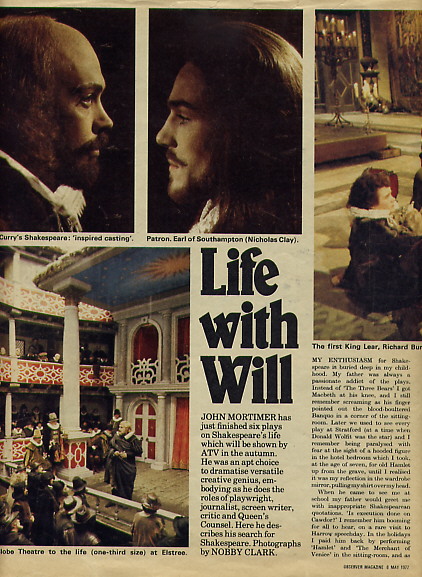

By early spring

last year the Globe Theatre had been built on the lot at Elstree, a one‑third

life‑size replica which must be one of the most beautiful and expertly made

sets ever constructed for television. It was thrown open by Lord Grade (a

ceremony the poet couldn't possibly have foreseen, even during his richest

fantasies on the subject of immortality), who then left Peter Wood and me,

with the constant support of Cecil Clarke, the producer, to pursue our invention

unhindered.

I had now worked

my way back to the first play, which deals with an entirely fictional friendship

between the young Shakespeare and the established Marlowe. Marlowe said

outrageous things in company, reporting an 'extraordinary love' between

Jesus Christ and his 'Alexis' John the Baptist (Merlyn Rees would have had

him deported for less) as a dinner party sally. The inquest on his violent

death by dagger in a Deptford inn also provides an insight into his extraordinary

character. Shakespeare the Survivor must have kept quieter in company, and

his life was apparently guided by a general determination to die in bed.

So there seemed room for an argument between the playwright's dedication

to his craft and his ever‑present temptation to act out his dramas in the

real world. The confusion was exaggerated in those days when the Elizabethan

man of action frequently behaved like a character in one of Shakespeare's

plays (Essex quoted Henry IV on the scaffold, Southampton wore a Hamlet

suit of black when imprisoned in the Tower). Only Shakespeare himself forever

resisted the temptation to behave like a Shakespearean hero.

Ian McShane, darkly

handsome, came back from America to play Marlowe. By an inspired piece of

casting the star of 'The Rocky Horror Show', Tim Curry, whose eyes might

have come straight from the 'Flower' portrait, was Shakespeare. Shooting

began in the heat‑wave, when Peter Wood arrived and electrified the studio.

He sat in the control room with a silver Thermos of coffee, an assortment

of pills and sweets, bottles of bay rum to rub on his head at moments of

tension, and urged the actors to behave like real people. 'It all gets terribly

slow once you've got your Elizabethan knickers on!' he warned them.

The actors responded manfully

to Peter's tirades of flattery and rebuke; but the audience in the Globe

Theatre were less involved. Although the director, wearing little but a

pair of Y‑fronts and a gaucho hat, shouted stimulating directions through

a bull horn, they began to melt away in the hot weather. It was noticed

that the benches were thinning, and assistants were sent out into Elstree

to round up sullen groundlings who were pushing wire wheelbarrows through

Tescos or shopping in Boots, still wearing full costume.

In the autumn Peter

Wood went off to direct an opera in the Arizona desert. Other directors

came, and the plays, which of course took more than a month each to write,

became easier as I got to know the actors. A wonderful company was selected

as Shakespeare's fellow players, starting as rustic as the rude mechanicals

in the 'Dream', keeping hens and tethering goats beneath the stage of the

old Rose Theatre, and ending in scarlet liveries as the King's Men, with

well‑fed Burbage almost too fat for Hamlet, rogues and vagabonds no longer.

I was amazed at the perfectionism of Cecil Clarke: having worked for many

years with Guthrie and taught at the Old Vic Theatre School he saw every

shot, supervised every costume, and if a scene wasn't correct he went back

and had it redone. I also had the luxury of writing new scenes for the earlier

plays if they were not altogether clear or correct in performance.

At last it was

over. The Globe became filled with mud, and then ice, as the actors shivered

over 'Hamlet', the last play we show in an open theatre. There was a party

at which three secretaries arrived dressed as Queen Elizabeth, talking the

language I had tried to write, based on Shakespeare's prose and the Queen's

own speeches. Nick Clay, who had rioted through London as the arrogant young

Earl of Southampton, changed into his Palm Beach shirt, kept on his earring

and drove off in his multi‑coloured car. Tim Curry locked on with large

eyes, finished with the Observer, the Survivor, the Nurser of Bitter Memories,

the Great Comedy Writer and the Post of the world's most terrible tragedies;

the man whom everyone loved but no one really knew.

As they were to

be plays and not documentaries we were guilty at times of forcing history

into that most compressed of all dramatic shapes, the hour‑long telly play.

We brought forward the death of one of the actors who left money to Shakespeare

into the time of general questioning and terror after Shakespeare's company

were suspected of giving a special performance of 'Richard II' to encourage

the Essex revolt. The dates of some plays' composition have been telescoped;

but really the invention is in areas where the historian can only guess and

the dramatist must create. So the principal story of the plays is the changing

relationship of two men, poet and patron, friend and lover, Shakespeare and

Southampton in youth and early middle age.

The plays end when

Southampton also lost sight of his friend, in the dark shadows of Jacobean

England, when the drama came indoors from the daylight of the theatres,

and Shakespeare began that final journey in which he seems isolated from

his friends and family and all that happened to him took place behind that

high, walled forehead where neither I nor Peter Wood nor Cecil Clarke, with

all the sets that ATV built so expertly, could presume to follow him. However

my television plays about him may be received, living with Shakespeare has

given me one of the most undilutedly happy years of my life.

from The Observer Magazine

8 May 1977, pp.32-37